Gurdjieff vs Asia

2 Models of 3 Wisdom Centers

How many subjective parts do you have? How many different styles, modules or lines-of-intelligence operate in a normal human being? These are important and interesting questions that we do not ask often enough.

Whenever I give “introductory talks” about Integrative Philosophy, I always employ a sliding scale of selves. The simplest place to start is imagining that we are each one single evolving entity who is roughly analogous to our general cognitive capacity, worldview and values.

Next is two variables. Tracking the differences between our “talk and walk” is very relatable for most folks. It might be quite important to tease apart our embodied emotional understanding (or perhaps our motivating moral instincts) from our abstract capacity to recognize and articulate patterns.

If we have enough time in the seminar, I might end up with the 7-fold model of the neo-Hindu “chakras” or even a dozen speculative Howard Gardner style “intelligences.”

However, the most common and classic number is 3 — heart, mind & body. These are arguably the basic minimum psychic components that are in play throughout most of the world’s wisdom-traditions. So today I would like to open up an inquiry into the relationship between two different styles of treating humans as three-centered spiritual organisms. And I will approach this through a symbolic contrast between Gurdjieffian & Asian mysticism.

Who is Gurdjieff?

He was a very influential & complex Greek-Armenian spiritual teacher in the early 20th century. Although he lived and explored in Asia for many years — studying Indian, Tibetan and Chinese dharma practices — Gurdjieff’s own later teachings contain both a deep continuity with historical esoteric lineages and a number of radical innovations that are peculiar to his own vision.

Noteworthy here is his reframing of the “three spiritualized parts” of heart, mind and body within his integrative and maturational practices. His analysis of the neurophysiological and energetic correlates of these three subjective functions are divided differently than in many traditions.

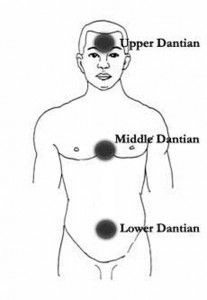

In Asia (but, of course, not only Asia) there is a long history of associating our emotions with the upper chest & our physical intelligence with the general vital region of the lower abdomen. China and Japan, in particular, have spawned elaborate teachings concerning the hara — located typically in the deep belly below the navel.

This emphasis on the embodied wisdom center of the abdomen is widespread today. It strikes most of us as very intuitive. It dovetails nicely with our modern colloquial discourse about “trusting the gut” and also with many interesting scientific findings about the neural networks woven throughout our intestinal and digestive processes. Anecdotally, I have heard that the number of neural connections in that region of our body approximates a cat’s brain.

We may literally have an independent mammal mind operating in our bellies.

There is also a large mass of neural tissue around our physical heart which is believed to play a significant role in the production of the bio-electromagnetic field of the human body. Sensitive electrical instruments can detect the human heartbeat up to a dozen feet away from the body. So there is a very plausible argument that head, upper chest and lower abdomen are the privileged centers, the interdependent intelligences, within the human psycho-organism.

What critique could be offered to this? And what alternative does Gurdjieff propose?

The first analytical challenges might come from the yogic 7-center model. It would incline us to ask why these particular three functions are being privileged in certain lineages. Without straying too far into Oriental stereotypes, we might nonetheless be legitimately suspicious of the fact that the “Chinese model” does not strongly promote individual independence (solar plexus chakra) and personal expression (throat chakra).

Similarly, we could consult the world of Dr. Wilhelm Reich — the philosopher and psychoanalysts who did pioneering work in the attempt to scientific articulate a model of bio-energy. He had his own method of dividing the body vertically into relatively independent functional “segments” and he put a lot of work into considering how the psychophysiological suppression of individualism & sexuality played a role in mass-oriented, quasi-despotic, exaggeratedly patriarchal and highly sentimental populations and states

These two lenses, among others, offer us the chance to critically inspect the potential bias and idiosyncrasy that could be implicit to the privileging of the upper chest and lower belly as human energy and intelligence functions.

To what degree is the belly indicative of a fundamental center of the self and to what degree does its emphasis reflect peculiar historical and cultural preferences?

To what degree are our subtle energies modulated universally through head, chest and belly and, conversely, to what degree are those peculiar forms of subtle energy embedded in and privileged by particular styles of people operating in particular social systems?

It’s uncertain but definitely worth considering.

Keeping this kind of socio-critical awareness in the back of our mind, let’s examine Gurdjieff’s alternative model. It may be either better or worse than the standard version but it at least offers a comparative space that holds open a further inquiry.

Gurdjieff strongly emphasized the need for a “harmonious development” of mental, emotional and physical intelligences. These, he believed, can be voluntarily and progressively integrated into a generic quality that he calls being. However, he does not link these functions to the same three-storied vertical anatomical zones as in common in many of the ancient traditions.

While the “Asian” model conceives the human being as a kind of armless and legless creature, the Gurdjieffian version draws its distinctions between the head, torso and “spine” (or extended autonomic nervous system).

So the first point of difference is that the body-wisdom is not represented, for Gurdjieff, by the lower abdomen but, rather, by the peripheral functions of the integrated sympathetic & parasympathetic brain networks extended to the periphery of the organism. In his work as a hypnotherapist, Gurdjieff was keenly interested in the processing-and-signaling systems of “subconscious” neuro-muscular intelligence (very efficient, rapid associative systems similar to Kahneman’s notion of System 1) which express themselves in the micro-gestures and behavioral habits of the limbs and semi-voluntary surface musculature of the body. In this approach, somatic wisdom is epitomized not by gut instincts or the grounding influence of the “core” but, instead, by the decentralized intelligence located in-and-as our biological engagement tools (limbs, fingers, muscular responses, sensory organs, tendrils, etc) — mutually coordinated in the primitive brainstem and spinal cord.

From the bio-psychoanalystic viewpoint of Dr. Reich, we could postulate that the centralized belly is a socially safer zone — less problematized by the decentralized and sprawling spider/tangle of our expanding and contracting autonomic-vegetative networks.

Gurdjieff’s approach to “emotional intelligence” does not contain it in the upper chest. Rather he seems to associated it more broadly with the whole collection of sensitive organs on the torso.

According to Gurdjieff’s cryptic masterpiece Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson, the whole torso consists of organs with neural intelligence networks associated with them. He speculates that under healthy, mature cultural conditions these organ-brains are integrated into the solar plexus. All of these sensitive systems are collectively regarded as “the heart.”

This decentralized pluralism — in which we are encouraged to lessen our tendency to associate subjective capacities with particular physical localizations — seems to be implied even by more elaborate notions of Traditional Chinese Medicine in which all major organs have informative feeling qualities.

Many schemes and arrangements, of varying style and complexity, can certainly be useful tools for organizing our expressive and integrative potential as spiritualized organisms. So this text is only to mark that there is an inquiry waiting to be opened.

Anyone exploring the tripartite model of human spiritualized intelligence will need to reckon, one way or another, with the parallax between these two models of heart/mind/body. Is one model more correct and comprehensive? Do they lead to different conclusions or converge into a common practicality?

And are there other versions of integrative threeness that we should be taking seriously?