Ordeal-ology

Let's Start Figuring Out Optimal Suckiness

(There is, of course, an audio version of this article, read by the author, available for paying subscribers — who also their articles earlier & coated in golden pixie dust).

I. Our Phantasies of Stress-Based Engagement

AMC’s The Walking Dead dominated television in the 2010s. It was an unexpectedly mainstream take on the ultra-violent genre of zombie apocalypse fiction. We seem to love the Apocalypse. People still tell me that my Apocalyptarians presentation on Limberg’s Stoa platform was “peak Layman.” But there is something perverse about apocalypse fiction. It goes way back.

From the Norse Ragnarok to the Christian Book of Revelation, there have always been people warning us about imminent social collapse in a very suspicious manner. They seem a little bit too “into it.” Subliminally eager. There is an indulgent aspect to the concept of the coming Great Ordeal. And the people who most strongly try to convince us of this inevitability are often those who secretly get off imagining themselves thriving in a post-social barbarism. Preppers figure it could be their time to shine. At last!

Here’s what those perverts might be right about: thriving requires ordeals.

The moral of every The Walking Dead episode is that people are not clear enough, hard enough, or killer enough, to protect what matters. We do not have enough grit in our souls. The modern curse of wishy-washy liberal altruism, self-destructive ethical hypersensitivity, and cowardly narcissistic cringing is always getting the wrong people killed on these shows.

Maybe this is a message that human beings are trying to send each other through the medium of large-scale art & entertainment. Perhaps it represents a valid developmental intuition that gets mixed up with some accurate concerns (e.g. there are many fragile areas in the global economy and many accumulating risks from business as usual) and with our perverse lust for imminent disaster.

I am going to argue (or perhaps “ambiguously pontificate”) that our current cultural set-up is not providing humans with adequate transformational distress. However, we need to clean up and professionalize our thinking in this area. Vaguely inchoate anti-modernist and anti-civilization instincts are not going to get the job done.

We need to be smarter about this because we do not really want a socio-material apocalypse and we do not really have any clear sense about what kinds of ordeals are needed to strengthen and transform us. How often should we be distressed? At which intensities? What does it take to effectively assimilate them?

In short:

Do we have an ordealology?

II. The Emerging Dharma of Creative Misery

The groundbreaking 1990s stream-of-consciousness “sketch comedy” series Mr. Show featured a famous scenario in which young children were being scientifically traumatized. There was a fake TV ad for a special school promising to provide your hapless children with just the right type & degree of pain, upset, and deficiency — depending on your goals.

Do you want your daughter to make breakthroughs in biochemistry? Or your son to become a prominent political leader or radical CEO? Our scientists will hurt them appropriately for whatever high-achievement outcome you desire.

This is a very interesting idea. It feels simultaneously horrible but also vaguely correct. (Of course not! But maybe…?)

What, when, and for whom is which type of distress most useful? Very few people have been formulating and asking questions like these. We need to start thinking coherently about this stuff rather than abandoning it to apocalyptic entertainment, sadomasochistic self-help warriors, and self-justifying insensitive abusers. And, honestly, it looks to me like the first signs of a 21st-century ordealology have already begun to emerge:

Carol Dweck’s Growth Mindset solidified the idea that capacity and self-worth in children is not related to positive self-esteem feedback (which rewards them for their mere presence and innate characteristics) but rather to environments that reward difficult efforts — especially efforts in areas where the child is not already competent. Successfully navigating situations that make you feel inept, unskillful, and frustrated is where real self-esteem grows.

Nassim Taleb’s Antifragile attempted to philosophically and statistically clarify the important role of “post-traumatic growth” in helping organisms (and societies) prepare for the unexpected shocks and inevitable entropy of the future.

Studies on the famous “Ice Man,” Wim Hof, have helped clarify that our bodies require periodic intense distress (not low-level ongoing distress) to heal and maintain self-regenerative homeostasis — as well as to activate impressive alternative capacities.

Leading-edge communities focused on spiritual, philosophical, and cultural development have increasingly begun to promote the importance of “difficult conversations” and “hard problems” and “staying with the distress.”

These are a few of many signs that the 20th-century’s War on Stress, and its fetishization of comfort, are growing beyond themselves toward a new appreciation of the role that angst might play in health, learning, and meaning. And yet considerable intelligence is required to make sure that this “revaluation of suffering” does not devolve into abusive, numbing, socially regressive, or otherwise counterproductive and naively simplistic promulgation of trauma and distress.

The Finnish people famously claim to have a fabled quality called sisu (roughly equivalent to the American frontier concept of “true grit”). It is inspiring but imperfect. Anyone who knows contemporary Finns can attest to the fact that they have been awakening to a new complexity in this regard. On the one hand, there are the real virtues of rough work, persistence, vigorous engagement, and “toughing it out.” That’s how you get Vikings to row across the North Atlantic. Yet on the other hand, this Scandahoovian (sic) virtue coincides with an intergenerational difficulty in nurturing themselves, expressing emotional richness, taking deep joy in existence, valuing personal outcomes, minimizing domestic trauma, and training people to thrive in a world that exists beyond ice fishing, mining, communist politics, and snow-covered forestry.

Their struggle is our struggle.

How do we begin a scientifically-informed New Wisdom capable of constructively distinguishing between self-eroding distress & self-flourishing distress? I see three major areas, seemingly unconnected, that are beginning to give us the tools to organize our thinking about an Ordealology:

(i) Philosophy of Complex Systems. The study of complexity (distinct from complicatedness) has begun to describe how adaptive living systems maintain themselves “far from equilibrium” through relationships, exercises, and absorptions. Systems that work with chaos, and work around disruptions, provide a new way of thinking about growth, learning, regeneration, ecosystems, non-conscious intelligence, and the principles through which organic evolution has made an engine out of unpredictability. We are collectively clarifying an objective and dynamic set of concepts for making rational sense of why (and how) some systems degrade under the effects of stress, time, and shock — while others flourish for exactly the same reasons.

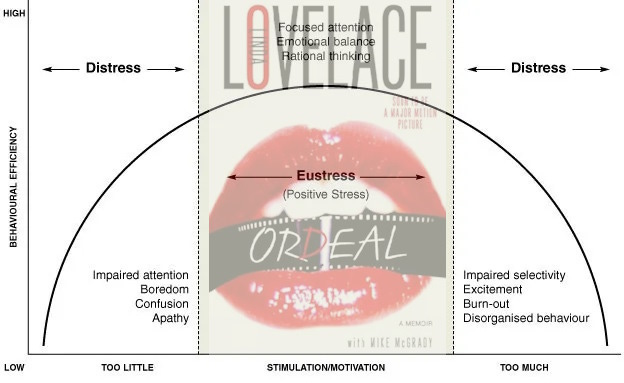

(ii) Sports medicine. Performance-oriented biochemical and neuropsychological research (from the lab to the locker room to the “bro-science” podcasts) have been accumulating quantifiable knowledge about the role of specific kinds of stressors that can accelerate healing, increase capacity, facilitate skill development, and evoke flow states — in distinction to stressors that undermine all those functions.

(iii) Bondage, Domination, and Sado-Masochism (BDSM) communities. For several decades the civilized world has had specialized social spaces attempting to stabilize therapeutic, self-exploratory, and pleasurable variations of voluntary and mutual participation in torment, bondage, submission, physical intensities, etc. These communities (with which most of us have no direct involvement) have been evolving principles of ethics, consent, and safety around public engagement with distressing forms of stimulation. Many of them are very professional in the use of rules and contexts that ensure that pain, humiliation, and excess are likely to be catalyzed into pleasure, growth, or insight.

These three disparate fields of cultural activity are seldom grouped together. Perhaps this is the first time? Yet I would argue that they are collectively producing the initial requirements we will need for a new practical science of constructive ordealology.

Drawing from principles shared broadly across these different contemporary domains of human exploration, we begin to think through the beginning of a wisdom of productive distress. One that neither regresses into infantilizing cultures of narcissistic comfort nor into toxic cultures that enshrine and protect abusers and self-harm.

The goal of this article is to set you thinking towards a new and shared cultural ethos in which we can understand and deploy the generative form of the ordeal.

But, then again, how new is that?

III. Reimagining Shamanic Ordeals

We retrospectively envision an archaic pre-historical nomadic humanity (the longest period of human culture) that exhibits a pattern of maturational and visionary “ordeals.” To some unknown degree, these ordeals were generated, tweaked, and overseen by an organic esoteric caste that today we often call “shamans.”

These ordeals seem to have involved fasting, sleep deprivation, entheogens, physical disorientation, uncanny isolation, piercing and marking, stillness in odd positions, claustrophobic spaces, grieving, and ritual humiliation.

Under shamanic supervision, these kinds of practices were performed during a variety of special conditions, including:

maturational life transitions such as childbirth, puberty, adulthood, marriage, mourning, becoming an elder, joining a tribe, forming an alliance, etc.

seasonal holy days in which the human community reorients its participation in the ecosystem according to a “sacred calendar”

periodic social re-sets (such as rituals in which the patriarchs and matriarchs are humiliated or temporarily stripped of status to ensure they do not get too fixed in their social roles)

opportunities for special insight, inspiration, or empowerment (e.g. during periods of collective uncertainty or as part of the special individual training to become a future shaman)

This general sense of anciently normal “managed ordeals” can help inspire us to think creatively about how we might socially instantiate appropriate opportunities for creative distress going forward. Currently, we seem stuck.

The ethos of hyper-individualistic Consumer Capitalism promises that we do not need any ordeals. Our outdated religious and cultural traditions offer mostly ineffective combinations of hazing and bullying that no longer seem to accomplish their ancient purpose. And our collective attempts to evolve a New Age religiousness have mostly resulted in ornamental and aesthetic rites that amplify positive aspirational emotions without harvesting stresses or frictions.

Outside of the social stress of wedding-planning, or perhaps putting up with extended family at holiday dinners, we do not involve the specific element of intentional difficulty in our popular rites. Deliberate suffering does not play a significant and overt role in school graduations, the beginning or ending of female menses, becoming a man, retiring, attending a funeral, embarking on spiritual life, etc.

One of my former Buddhist mentors used to tell us that he was made to stand in a difficult “horse stance” for many hours before being admitted to the religious training temples. I always thought: Why aren’t you making us do that?

It is certainly useful to make some things more accessible, easier, and less traumatic but what do we risk losing in the process? And what sorts of principles would be needed to revive intentional difficulty in a less stupid form?

Kintsugi is a Japanese art form that repairs broken items in a way that highlights the patterns of breakage — often by filling them with gold. It increases the value and beauty of an object by demonstrating that it is now on the far side of a distress.

IV. Trigger Warnings

Most people have heard that the Alpine philosopher Frederich Nietzsche said, “What does not kill you makes you stronger.” We also think there is a military training slogan that goes, “Pain is fear leaving the body.” Inspiring stuff. However, it needs to be significantly elaborated, organized, and contextualized. Obviously, some pain will simply destroy you. And certain things that do not kill you may nonetheless leave you weakened, traumatized, and broken.

These slogans suggest a general attitude of antifragility that can take advantage of certain moments of intense discomfort — provided that these moments do not fundamentally sabotage our functional capacities (physical, emotional, intellectual, moral, spiritual, etc.) or otherwise generate turbulence in our lives that does more harm than good over time. But under special conditions, complemented by appropriate nourishment and care, we may grow strong through pain and even establish post-traumatic growth.

So the project for we proto-ordealologists is to increase our discernment. We need better practical and philosophical clarity about when pain is merely destructive and when it might be constructively transformative. Many kinds of suffering seem needless and unproductive — and even in need of better advance warning about how to avoid them. It is a great modern achievement to warn each other about “toxic” effects that are camouflaged in our foods, homes, social assumptions, scholastic contexts, bad habits, etc. yet “trigger warnings” are notoriously easy to mock.

We think that narcissistic, coddled adolescents in Universities are fragile babies, raised online, unable to tolerate even symbolic discussions about violence, sexuality, power, taboo words, or the horrible complexities of the real world. There is a lot of truth in this critique. And certainly, there has been a corporate undermining of our higher education system that has led to a “customer is already right” paradigm — in which teachers are just supposed to provide a comfortable enjoyable space rather than any culturally challenging education or socially constructive forms of exposure therapy.

Exposure therapy? That’s right. Exposure therapy (as frequently recommended by arch-dubious characters like Jordan Peterson) is the voluntary contact with things that cause us emotional and psychological distress. Afraid of snakes? Study snakes. Touch a snake. Etc.

The key to doing this wisely, however, is that it must work (a) by degrees (b) by agrees. That is you have to agree to do it. You only get retraumatized and phobically exacerbated if a “helpful” person tosses a snake on you when you are not ready. And there is no shortage of people who want to help in this counterproductive fashion.

Sadistic helpers exist in many forms and frequently they have no conscious malevolent motive. They believe in their own benevolence and socially acquired idealism but, mysteriously, this always seems to justify them verbally, emotionally, or physically accosting other people.

Perhaps they have psychological blocks that inhibit the recognition of anything hostile or disruptive about their own intentions. Perhaps they have been raised in families in which it is customary to express “support” and “love” by communicating harm. Not just the gross forms of assault and molestation but all the subtler ways in which they demean your choices, urge you to eat too much, tacitly endorse date rape, make hyperbolic claims about which population segments should be punished and eliminated, etc. Yet all the while, as far as they can tell, they are trying hard to love you and serve ancient normal human values.

A special form of the sadistic helper is the asshole guru.

The asshole guru is a person who wants to use force, persuasion, and interference to “push you” into overcoming your ego, habits, and limitations. At the same time, they neglect your consent, ignore power asymmetries, and fundamentally cannot separate their impulse-to-dominate from their legitimate drive-to-help-you-transform.

So the field of ordealology has to work around, and with, the twin problems of culturally-supported weakness & culturally-enabled domination/interference. And it must learn to ask itself questions like: Where on a spectrum from tolerated weakness to destructive interference can a voluntary individual most benefit from distress at any given time?

For any particular person:

how frequently do they need constructive distress?

what practices best prepare them to assimilate their next distress?

how much comfort and restoration is needed between attempts?

how much and what kind of consent is needed to make the distress useful?

how much latent nihilism or self-harm must be accounted for in their psychology?

And beyond the individual, how do societies and intentional communities (a) intelligently harness the dynamics of ordeal to help produce bonding and mutual group spirit, and (b) provide adequate interpersonal coherence and support that allows individuals going through ritual or circumstantial distress to accept, internalize, and assimilate those intensities?

V. Frontier Mentality

Novelty is a pain.

Like all pain, we need to figure out when it is useful or useless. We should not always bother ourselves with the next “new thing” and there is scant reason to assume that this year’s new Ford Taurus or this month’s Google Chrome update or the younger generation are likely to be improvements.

Our society fetishizes novelty because our economy wants you to abandon your existing habits in favor of the next new product, event, or service upon which to spend your state-generated and corporately-mediated social credits ($). We learn ideological instincts that tell us we should travel, constantly check the news, switch things up, get a new look, read the current best-seller, and find out if anything exciting is going on in town lately.

This novelty trap keeps us relatively superficial and exploited but it is also true that there is real psychological and social value in exploring. Species that exhibit higher rates of innovation and exploration increase their odds of locating and exploiting new resources which, in turn, enables them to prosper and grow.

Modern and global human civilization has learned to praise innovators but, at the same time, our contemporary social systems seem oddly stagnant in numerous ways. Many countries are peculiarly reluctant to implement new technology, take new scientific discoveries seriously, or secure the kind of robust social safety net that allows more people to take cultural and entrepreneurial risks.

Instead, we make flat roads, smooth sidewalks, and temperature-controlled offices. We eat the same few addictive foods in endless grocery store cycles, and we get insulted if we hear news that disagrees with our existing biases. Theorists have argued that we have lost our exploratory mode. We are not in a good relationship with novelty, frontiers, nonlinearity, wilderness, and the future.

It is not just that we never got those flying cars, jet packs, and geodesic houses that seemed so imminent in the 1950s. Probably Obama’s fault. And it is not just that our four-year election cycles prevent us from establishing any consistent long-range planning for the emerging territories of tomorrow. Our political parties are not putting forward any inspiring long-range visions and anyone who suggests a non-regressive upgrade to our social, economic, political, or material infrastructure is accused of frothing idealistic radicalism.

We may have lost touch with frontier mentality.

Frontiers and Ordeals are deeply entangled. They represent territories of potential growth, learning, and empowerment that are separated from us by thresholds of unknown and uncomfortable experiences.

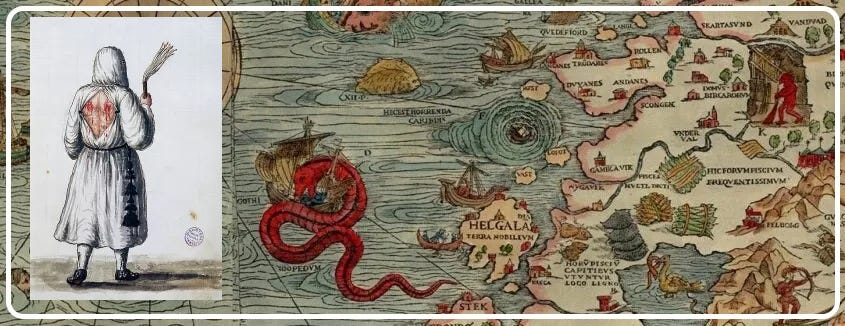

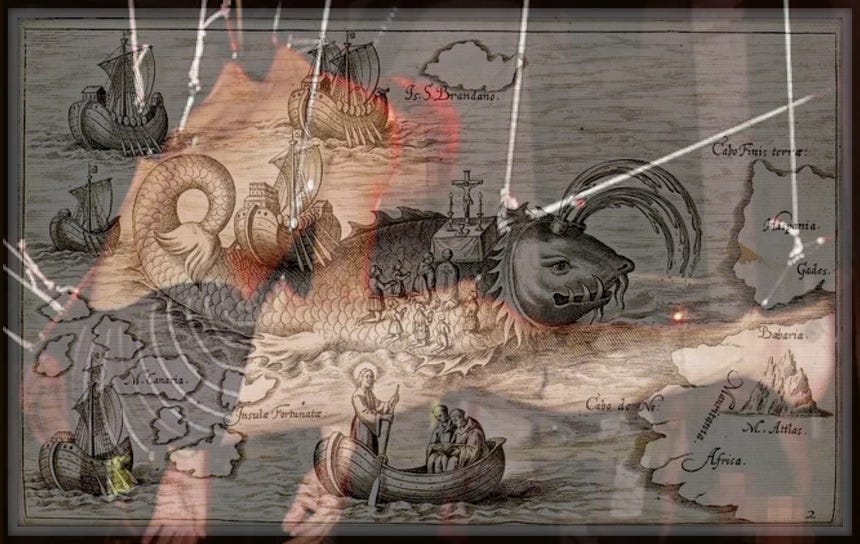

Antique maps charmingly included evocative warnings like hic sunt dragones ( “here there be dragons”) to indicate the limits of the explored world. Beyond those markers, we face a different relationship between Order & Chaos. Efforts of preparation, uncertainty, courage, and conflict are needed to separate opportunity from hardship in these unexplored but potentially regenerative territories.

If we are to retain & regain our collective instinct for frontiers, futurism, and self-transforming upgrades, then we need to go beyond just stabilizing our nervous systems. We need to venture into territories where peculiarity, ambiguity, angst, and disruption provoke our exploratory modes — just as the “micro-harm” of acupuncture needles might trigger the body to release endorphins and activate its regenerative systems.

We typically relate to the new, alien, other, unknown, and complex as temporarily frustrating conditions but this can be modulated just as we might retrain ourselves to enjoy an invigorating cold shower or ice plunge. Such shifts in attitude are aligned with the principles of the growth mindset but also with the sense of adventure that most of us seek out in our common fictional scenarios.

A haunted house, creepy cave, secret tunnel, or undiscovered country presents a thrilling field of exploration that is inevitably guarded by a gargoyle-like threshold of fear, pain, friction, and uncertainty.

At the beginning of this article, we considered how The Walking Dead and other forms of apocalypse porn are compelling (in addition to their writing, acting, and directing) because we displace onto them our need for difficult encounters, ordeals, and the regenerative experience of challenging frontiers.

Why was E. L. James’ 50 Shades of Grey such a popular novel?

It is not merely because so many modern women enjoy story-based erotica featuring dominant men. There is also a deep curiosity about how our nervous systems relate to the physical and emotional intensities of submission-play and excessive sensations. Where do you have to go in yourself to assimilate such experiences? And what version of yourself exists on the far side?

Fictional associations between libidinal energy and intentional submission to ordeals are one of the safe ways for people to explore a lingering sense that, despite their daily attempts to resolve stressful situations, some other useful possibility exists specifically within situations of temporary acute distress. Readers and viewers of such material could be considered as instinctive amateur proto-ordealologists (IAPOs).

These impulses around fiction should not be studied merely in isolation but placed in context with other cultural phenomena such as dopamine fasting. Dopamine fasting is a movement that promotes the deliberate refusal of comforts, pleasures, addictions, and hyperstimulation to “reset” our internal reward system. Originally it was proposed by Dr. Cameron Sepah as a way to get some leverage over negative habits but it immediately attracted large numbers of people who feel strongly that tactical anti-pleasure is necessary for contemporary sanity, growth, and meaningfulness.

We need to struggle with our neurochemical pleasure signals to regain the adventurous frontier sensibility that our world is a fresh, open realm that rewards participatory exploration.

Dr. Cadell Last from The Philosophy Portal has written compellingly about the perverse logic of a neo-liberal capitalist system in which our repetitive drive for pleasure, meaning, and sexual identity becomes linked to phenomena that do not reproduce themselves, do not strengthen our culture, and do not restore our open-ended wellbeing. His psychoanalytic sociology faces the question of how we grow past this cul-de-sac of non-productive comforts and pleasures without regressing to a naive premodern pseudo-conservatism.

I speculate that certain forms of deliberate displeasure, in which we intelligently connect our psychological drives to ritual ordeal and inner struggle, will play a key role. It would have to be encouraged by cultural authorities and practices that approximate religion. This is where Cadell’s call for a new theopolitical commitment overlaps with the work that Brendan Dempsey and I have been doing on “metamodern spirituality.”

Religion (-ishness) has traditionally provided the “extra reason” for busy human and desiring agents to engage in fasting, celibacy, unnecessary labors, voluntary disruption of business-as-usual, pilgrimages, remorse, dark nights of the soul, etc.

One of religion’s functions — whether we are thinking about diverse, organic, and shamanic religious streams or more institutionalized classical/traditional models — has been to store, promote, cultivate, and sanctify our collective and personal practices of constructive displeasure.

To domesticate distress as a tool for regenerative homeostasis, personal discovery, flow state learning, catalyzing of peak states, cultural bonding, increased alertness and immune response, antifragile preparation for unknown futures, and the refreshing of the hormonal chemistries required to produce meaning & value within organisms such as ourselves, we need not only the diverse data, careful discernments and plausible theory for an ordealology, but also experts and cultural contexts that can constantly be evaluated for their capacity to productively oversee our deployment of distresses.

VI. Inner Practice

In the cinematic origin story of Deadpool (a subset of Marvel’s X-Men universe) our hero is taken to a special facility where he is experimentally subjected to numerous forms and intensities of direct pain. They are looking for the particular pain that will activate his mutant genes.

It is the same principle in Dune wherein a sister of the Bene Gesserit cabal may take the poisonous water of life and, if she can transform the pain and poison, she gains new access to intergenerational wisdom, insight & influence. Clearly, these are not real scenarios but what they present as fantastically exaggerated physical metaphors may be an actual subtle interior process that catalyzes human transformation.

Suffering, friction, and inner struggle (or whatever that is altogether) are key principles of ancient systems of spiritual development. From fasting, hanging on hooks, and self-flagellation, to letting the suffering of the world break your heart, to holding your attention on a chosen focal point no matter how much that sucks.

This is always at risk of coming under the sway of our stupidity (i.e. not thinking out how to have a better experience) and our self-loathing (i.e. the self-esteem issues that keep us addictively orbiting around the same forms of physical and emotional upset), but it nonetheless has profound potency. The angst between different behavioral investments, different internal sensemaking systems, or alternative values, is a highly charged condition of “contact between subjective sub-systems.”

This contact is like yoking (yo-ga) them together so that their degree of integration, coordination, or harmony increases. Yet this cannot be done merely nominally — as if I could simply “decide” to value conflicting inner processes. What matters is not the official recognition but the degree to which we can bear the intensity of the energy that needs to be exchanged between these systems to viscerally cultivate a metacognitive interbeing in ourselves.

You may have heard me say something like this before.

All of your usual angsts have the form of a di-lemma. Not just a homogenous swarm of bad feelingness but an actual circumstance of polarized disagreement between two or more of your parts. The problem is that — just like the two electrical terminals on a battery or the two phases of alternating current flowing into a light bulb — you need “something” to touch both of them in order to allow the current to flow through. You need a conductor or filament.

That filament is you.

Your intentional participation in the suffering provides the opportunity for the disagreeing neuroelectric and chemical behavioral systems to dynamically exchange and coordinate — leading to a more generalized, coherent “self” whose actions more fully represent your actual suite of values.

But how can you take advantage of this possibility? Is it just to be exposed to more suffering? No. Most of your suffering is stupid and useless. Or least it is an attitude of this kind that creates the opportunity for an actual ordealology that is not merely a pro-ordeal idiocy.

The special position, in which you activate whatever subtle mechanics are symbolized by crass comic book notions of “activating mutant powers,” is something we must individually and collectively speculate about and safely test. There are internal, external, and mutual dimensions that must be intelligently examined in order to start building a useful social lore about the constructive and voluntary deployment of ordeals.

We don’t need more suffering, we need better suffering.