The Political Ontology of Walkie-Talkies

A Glimpse at Two-Line Categorization Methods

This is part of a series of small articles, or probes, seeking for new, more effective ways of thinking about political entities, processes and forms of analysis. I am interested today in a two-valued form of developmental political analysis based in general contours of “integral theory.” But first let’s take a brief tour of the common existing methods of analyzing the electorate.

It seems that no one really believes that the political landscape can be neatly divided into two value-tribes (Liberals and Conservatives) represented by two official “big money” establishment political parties.

Whether we argue with our fellow partisans, seek refuge in third parties, assert ourselves as “independents,” or take temporary cynical pleasure in attacking all of the THEM, we seem to be weary of the simplistic dynamics of the duopoly. Even the mainstream media — who perhaps benefits most from the stress-based narrative of The Two Sides — seems to sense that they are standing on quicksand.

Most of us, in calm moments, have at least a slightly bad conscience whenever we use Left & Right as if they were sufficient to describe actual political sensibilities.

Existing Strategies for a Richer Analysis

The first attempt to get free of this limiting political Manicheanism is usually to add a degree of intensity. In addition to the left/right duality we start to speak of the “far left” and the “extreme right.”

Initially this makes a lot of sense. Folks are happy to think that, whether they be liberal or conservative, that they are reasonable, pragmatic centrists who might have more in common with each other than with exaggerated fanatics in their own party. However it may create more confusion than it solves. After all — who gets to decide what is radical? Doesn’t that designation always serve someone’s bias? And if the center left/right and extreme left/right are imagined as having a great deal in common with each other then… maybe the whole notion of the two sides was deeply flawed from the beginning?

And what do we make of the self-described centrist who is continually puzzled by the fact that people in the “far right” and “far left” keep attacking each other as if they were not really saying the same thing at all?

A more professional second attempt to make sense of the political sentiments of the masses involves the use of representational constituencies. Stop thinking about Left/Right and start thinking instead about “young people” or “Hispanics” or “white suburban female college graduates.” This involves a lot of mathematics and targeted polling. It has a certain expert aesthetic and academic charm. And it suits the temperament of cynical political operatives who function like advertising firms and are keenly aware their their “parties” are flexible and inconsistent when it comes to actually standing for particular principles.

Two major problems stand out with this approach. Firstly, it exaggerates the degree to which these population subgroups are homogeneous and psychologically motivated by representationalism. We gave them a black female candidate — why didn’t all black females vote for her? Secondly this kind of analysis, often stemming from elite institutions and wealthy political cities, frequently misunderstands their own class bias. In fact the living conditions of workers and the motivations of people in different socio-economic brackets are routinely ignored in a flurry of quasi-racist, quasi-sexist, quasi-ageist attempts to divide the population according to their superficial characteristics rather than their heterodox lived realities.

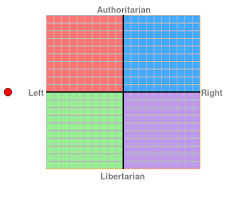

Another popular third attempt to overcome simplistic Left/Right analysis has produced the four-quadrant political compass. This gives us a little more traction by dividing liberal and conservative instincts into subdivisions based on the inclination toward centralized or decentralized political power. However if there is a problem in the original conception of Left/Right then such a problem persists herein. And there is no strong argument why the axis of Authority/Liberty is the other most characteristic major political polarization.

The political compass is vastly better than a simple left/right dualism but how much better — and whether it is going in the correct direction — remains to be seen.

An intriguing fourth attempt is associated with Nassim Taleb’s work on fractal localism. He is very concerned that we take scale into account. In several of his works he quotes the idea that a person can be “libertarian at the federal level, republican at the state level, democratic at the regional level and virtually socialist in his family life.”

Not only do people hold different polarities at different scales, the should do so — because the reality of forces and the necessary skills for values-based pragmatic decisions are different at each scale. An ant’s legs can survive being dropped from your roof but a horses legs will shatter. Size makes a difference. This seems like a crucial element of analysis but it quickly enters into conceptual territory that are hard for most people to follow and evaluate.

A fifth attempt takes the form of the “hidden memetic tribes” project. Here’s what they say of themselves:

“We used an advanced statistical process called hierarchical clustering to identify groups of people with similar core beliefs. This revealed seven groups of Americans―what we call Hidden Tribes―with distinctive views and values. Our breakdown of Americans into groups is tied to how they express their core beliefs, which isn’t necessarily aligned with conventional demographic measures like age, gender, level of education, or ethnic background. The result is a unique portrait of the American public that we believe is both more revealing and more actionable than typical surveys.”

So they create a spectrum that includes (what they call): progressive activists, traditional liberals, passive liberals, the politically disengaged, moderates, traditional conservatives & devoted conservatives.

This is an excellent step in categorization despite the obvious vagueness around who should be called “moderate,” whether or not people are “disengaged” for the same reasons and what counts as authentic “tradition.”

However there remain some serious problems here from my point of view:

Over-reliance on the conventional left/right framing of conventional status quo politics. (Even the form of their questions suggest their prior acceptance of the modern notion of a polarized politics. For example, one question in the hidden memetic tribes survey asks us whether we “agree” that the outcomes in peoples’ lives are primarily based upon their own efforts or upon luck coupled with external forces. My own immediate feeling is that external factors are objectively more important but that individuals ought to affirm their potential ability to determine outcomes through effort. There is no place for such an answer. Instead there is a predetermined implication that I have to side with either the supposedly conservative assertion or the supposedly liberal assertion. In this manner a great deal of information is omitted and the general notion of polarization, even though much more nuanced, is retained. )

Over-reliance on socially-contextualized verbal self-reporting about values. (The general logic of “how would you say that you feel about social values” is potentially very limiting in terms of political analysis. In 2016 & 2020 only a few American pundits even worried about the problem of the “shy Trump voter” who deliberately falsifies their probable voting patterns when these conflict with concern about their social image. Likewise, numerous show that ethicists and religious agents give much strong moral answers to questions without behaving more ethically in their actual lives. The odds that I simultaneously know my own values very well, want to share them, can share them (in such a way that they fit the proposed popular categories) AND are subsequently likely to act on them in a manner consistent with my statements is… dubious at best.)

The Many Stages of Terrorism

The American philosopher Ken Wilber wrote an analysis of terrorism based on the factors involved in his version of “integral theory.” To summarize it radically (sic), he concludes that the typical profile of the publicly dangerous terrorist — regardless of their cultural background or specific belief system — is that of Amber Cognition combined with Red emotional or moral drives.

Wait — back up. Amber and Red are typical short-hand code for proposed general operating systems in psychology and sociology. Among the more prominent operating systems are Barbaric/Impulsive/Totemic (Red), Ethnocentric/Loyalist/Fundamentalist (Amber), Rational/Modern/Linear/Professional (Orange) and Pluralistic/Ecological/Egalitarian (Green).

So Wilber is suggesting that the typical psychological profile of a terrorist is that of someone who intellectually endorses a monolithic, ethnocentric belief system while being emotionally motivated by impulsive, quasi-tribal habits of status-seeking, rebellion against large structures, “muscular” discharge, wild strength, etc.

Although we take it for granted that such internal structures are fluctuating, non-binding, non-comprehensive and evolving through different styles, nonetheless it is very suggestive to think of using two basic “developmental lines” to establish social profiles. To evade the problem of collapsing people into simplistic level-like categories, especially when there are potentially a large number of different inner developmental trajectories, it is likely that we should use at least two.

Taking after Wilber in this particular case, we can think of intellectual-verbal cognition and moral-emotional cognition. And in fact there are colloquial notions of this very thing. In English we say that someone doesn’t “walk their talk” when we observe that their moral consistency and emotionally-motivated behaviors do not strongly align with their statements about their values and purposes.

Walkie-Talkies

Developmental politics has to be keenly attentive to this relative gap between the Talk and the Walk. The rise of “reason” and “evidence” and “free thinking” in the enlightenment culture of modernity (and its ancient cultural predecessors) can be taken as a level of complexity in cultural history. We conventionally associate this form of cultural operating systems with virtues like self-analysis, consistency of thought, logical reasoning and the struggle to make more accurate statements about reality. That means, by extension, that we do not particularly expect that “premodern” cultural systems are strongly invested in the attempt to make rationally accurate statements about themselves or the world. It is perhaps more likely that premodern statements appearing to describe values and facts are actually heuristics or loyalty claims. The apparent freedom with which “conservatives” display cognitive dissonance and radical partisan shifts is often highly vexing to analysts who take the content of the claims as if they were serious statements about reality. A “mythic-member” can readily assert that she believes absolutely in peace — unlike her rivals! — and then segue smoothly into a call for all out war. These appear logically inconsistent because their consistency resides in their allegiances, not in the content of their statements.

Thus people who speak from premodern instincts are, in a sense, not even trying to give you accurate information about their values, beliefs and politics.

On the other hand, modernity is no angel. It may have “invented” the attempt to be rationally accurate but it also invented propaganda, marketing, targeted advertising, the rhetorical arts, etc. It turns language into a strategic game designed to leverage human behavioral weakness into successful political outcomes.

So if we have to be suspicious of (at least) modern and premodern verbalizations concerning politics then… there is no way that we can genuinely rely on people’s self-reported assertions. Evolution did not design us to tell each other the truth about our social views and likely moral behavior. It designed us to give ethical answers that serve our group identity while retaining the freedom act unethically. We are not limited to that kind of existence but we definitely have to take it seriously.

So unless our political analysis consists of at least two categories — joining some kind of behavioral analysis with self-confessed political value claims — we are unlikely to achieve even moderately good maps of the political landscape.

Examples

This article has already gone on long enough, but let’s take a few cursory glances at a two-line or two-value political categorization scheme might. In the last several American elections we see the current political dominance of four large blocs. The are trivially referred to as Conservatives, Republicans, Democrats & Progressives.

We might say Green/Green to describe people who rallied around Bernie Sanders because he seemed to authentically support pluralistic, ecological and labor rights. His consistent voting record backed this up. People who met him in person seemed to verify that his “vibe” was in accordance with his moral claims.

The mainstream media did not exactly know what to do with claims from many people in the Sanders movement that other prominent Democrats were “not really progressive.” This was seen as a form of self-destructive infighting or some kind of impossible purity test. In reality, it was the observation that most of the Green rhetoric was coming from Orange candidates.

Green/Orange broadly describes people who speak earnestly about progressive values but behave as members of the “centrist liberal-democratic establishment.” A lot of people did not feel like Hilary Clinton was an authentic feminist. Those same people do not believe Joe Biden really stands for working people. They may have resonated with Pete Buttigieg’s statements but did not “buy” him as the embodiment of those values — and were not much surprised when he dropped out to endorse (and be embraced by) the Biden team. Arguably even Barack Obama, whose cognitive skills are at least “Green” nonetheless appeared to act as a largely conventional, moderate liberal incrementalist who kept up the wars and made life easier for financialists and multi-national corporations.

Orange-Amber could describe people who graduated from professional modern institutions, wear nice suits and heads full of abstract numbers, rational in their rhetoric, strategic in their political game-playing BUT their overriding emotional motive seems to be returning the nation to a old-fashioned, ethnocentric, small government system dominated by a single hegemonic monotheism. The budget proposals of Paul Ryan, the folksy-aggressive internationalism of Ronald Reagan, the strategic racism of the Nixon administration, etc.

These Orange/Amberites constantly appear to be regressive fascists to the Orange-Green people while simultaneously appearing to be barely tolerable hypocrites to the Amber/Amber folks.

We would expect periodic uprisings within the American Republican party that take the form of Amber/Amber true believers and quasi-medievalists who are furious that the so-called “conservatives” or “republicans in name only” are too modern, too international, too liberal, too professional, not zealous enough, not Christian enough, not bombastic enough, too compromising, etc.

The most stereotypical public examples of the “Tea Party movement” and the “Trump voters” are close to what are called Devoted Conservatives according to the hidden memetic tribes classifications mentioned earlier in this article. But if we just listen to the passion of their particular social value claims, we miss things like the target of their political action (regenerative premodern culture) and the style of their articulations (making sense is not important). We miss the fact that, despite their claims of traditionalism and conservatives, they are highly adaptable and have no special understanding or commitment to the values of their ancestors. They are perfectly happy to elect an immoral, anti-Christian buffoon if he demonstrates symbolic allegiance and promises to accelerate the collapse of modern institutions. They are perfectly happy to read the story of Jesus as a scheme for getting rich and screwing over poor people. Etc. There is no logical or strong historical consistency in their behaviors.

To this analysis of the four major large blocs in recent American elections, we could then add other interesting combinations:

Orange/Orange

Green/Amber

Green/Red

Orange/Red

Red/Red

et al.

It is not my goal here to provide an exhaustive charting of these different combinations and various plausibly illustrative examples. What I want to do is simply introduce the concept of two-line analysis in political ontology as one way to approach the problem of escaping the dominance of (a) self-reported social value assertions (b) the latent dominance of the conventional right/left spectrum even in most analytic attempts to get beyond.